The next time you’re in CostCo, check out the employees’ badges. Right under the employee’s name, the badge say “Employee since _______”. Subtle, but powerful.

From what I know about CostCo, this is the real deal – they care about employee longevity, about treating people right, and about setting themselves apart from their peers. Barron’s called them the “anti Wal-Mart”, and with average 2007 pay of $17/hour – 42% higher than Sam’s club – there seems to be real truth to the story.

And then in the perfect twist, analysts like Emme Kozloff of Sanford Bernstein calls CostCo’s CEO Jim Senegal “too benevolent” and analysts at Deutche Bank complain that “it’s better to be an employee than a customer or a shareholder.”

(Now I’m supposed to drop in the chart of CostCo’s 10-year stock performance and show how it’s drastically outperformed the Dow and Walmart – each of which have offered a 0% 10-year return versus 80% for CostCo. So here’s the chart if you’re curious. But that’s not what’s on my mind.)

What’s on my mind is that, while I recognize that Jim Senegal has to do the dance of saying he pays employees well and treats them right because it’s good for the bottom line – because employee retention is higher, “shrinkage” (aka theft) is lower, and CostCo’s more affluent customers value interacting with happy employees – at some point we have to get to the heart of the matter.

When did it become accepted that actions that are right and moral – like paying employees a decent wage – have to be explained away and justified? When did we accept the notion that people should be moral in their lives but that the moment they show up for work their morality is subsumed by their obligation to maximize profits (whatever that means)?

All great companies exist to change their industries, to change the world, so the starting point is a sense of purpose and a willingness to play by a different set of rules. The question is: how far are we willing to go? Of course great companies should do great things for their shareholders and make lots of money for (all!) their employees, but the notion that it is better for management to be amoral rather than moral undercuts the foundation of our society, our values, what makes us human being.

It may sound naïve, but I find it ironic that in a country (the U.S.) where values, morality, and religiosity have such a central place in our culture, in the corporate mainstream – which is itself populated mostly by values-driven, moral, religious people – it is verboten to talk in any serious way about acting in a moral way because it is the right thing to do. Instead there’s this Texas Two Step, nudge-nudge wink-wink from CEOs to Wall Street to say “honest, guys, I’m just doing it to make more money!”

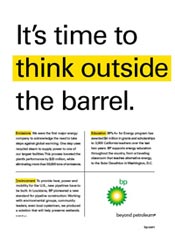

And then all of a sudden, a company that wins the Global Renewable Energy Award and that plasters magazines and billboards and tradeshows telling the world that “BP” stands for “Beyond Petroleum” is responsible for a 60-mile oil spill that will wreak unknown and unmitigated havoc on the environment, on wetlands, on marine life, and on us.

When will we as a society get to the point where we see that this is all connected?